Understanding Spatial Networks

Spatial networks are a simple but powerful way to describe how things are arranged in space when we do not have a map or coordinates to begin with.

Instead of recording where objects are, we only record which ones are connected or close to each other. These connections might represent wireless communication between sensors,

train routes between cities, or physical interactions between molecules.

In such a network, the objects are called nodes and the connections between them are called edges.

When edges tend to link nearby objects rather than distant ones, the network quietly contains information about space.

A central question we study is how much of that hidden spatial information can be recovered from the network alone,

and what properties make a network truly informative about geometry rather than just connectivity.

← Click!

In the interactive panel here, each point (node) represents a molecule, and each line (edge) represents a recorded interaction between nearby molecules.

If you zoom into the cloud of nodes and edges, you can see that edges tend to connect spatial neighbors.

This means that the network structure is correlated with physical proximity. Even when this correlation is imperfect,

it can still be used to infer spatial organization directly from the network.

Click! →

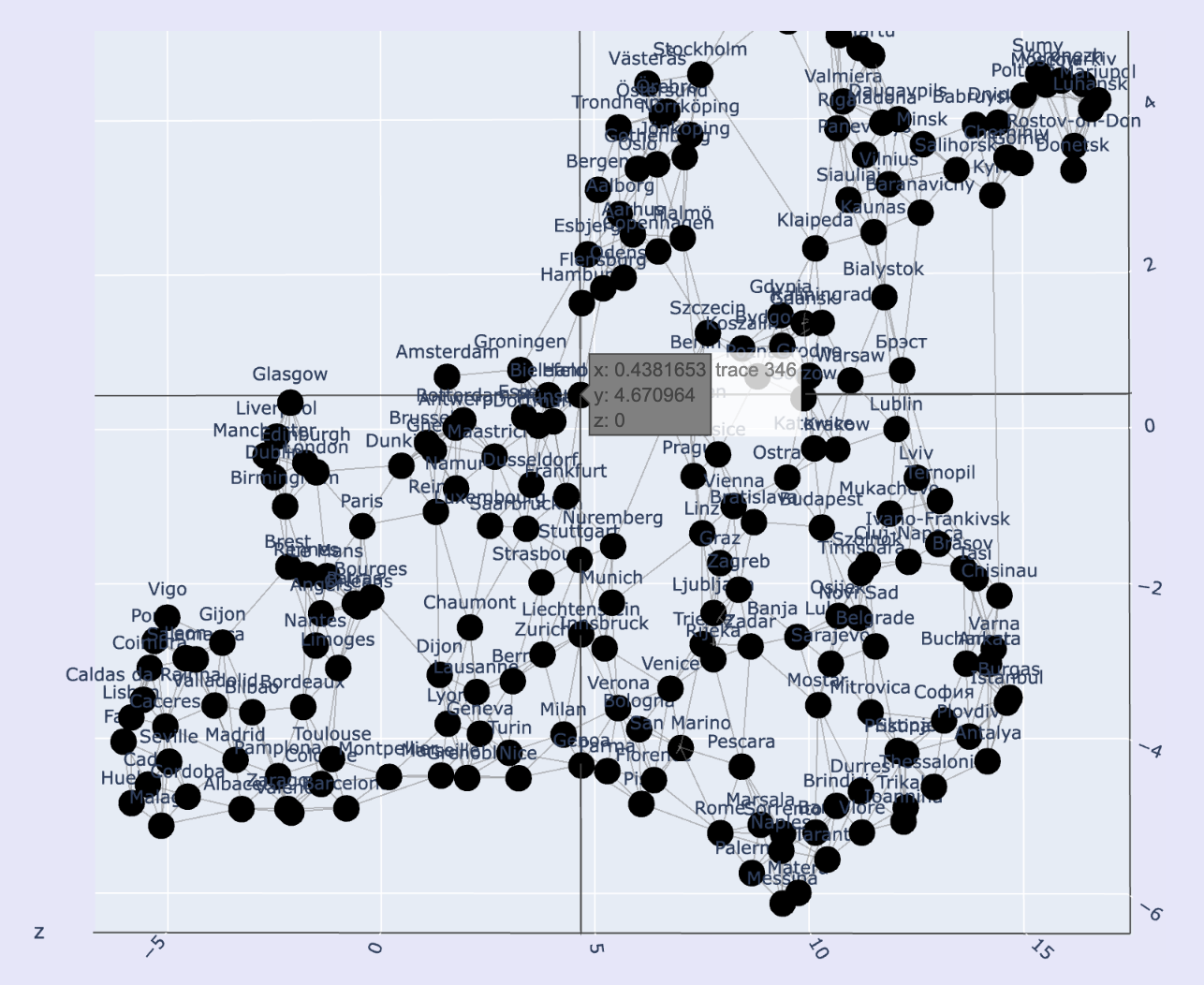

A big list of regional transit connections in Europe, e.g. Stockholm to Copenhagen or Paris to Lyon, constitutes a spatial network. A network is "spatial" if connections are related to the distance between objects.

So a list of regional transit connections in fact gives us information about where, in space, the cities are located relative to one another.

By optimizing for satisfaction of constraints, i.e. maximizing the closeness of connected nodes, we can recover that spatial information and generate an approximation -

have a look at the interactive plot here. -> We can see a few things - first of all the global positions have not be preserved.

However try reflecting and rotate this image, and you should be able to arrive at a more familiar map of Europe.

Remember that no information about coordinates was passed through to this reconstruction.

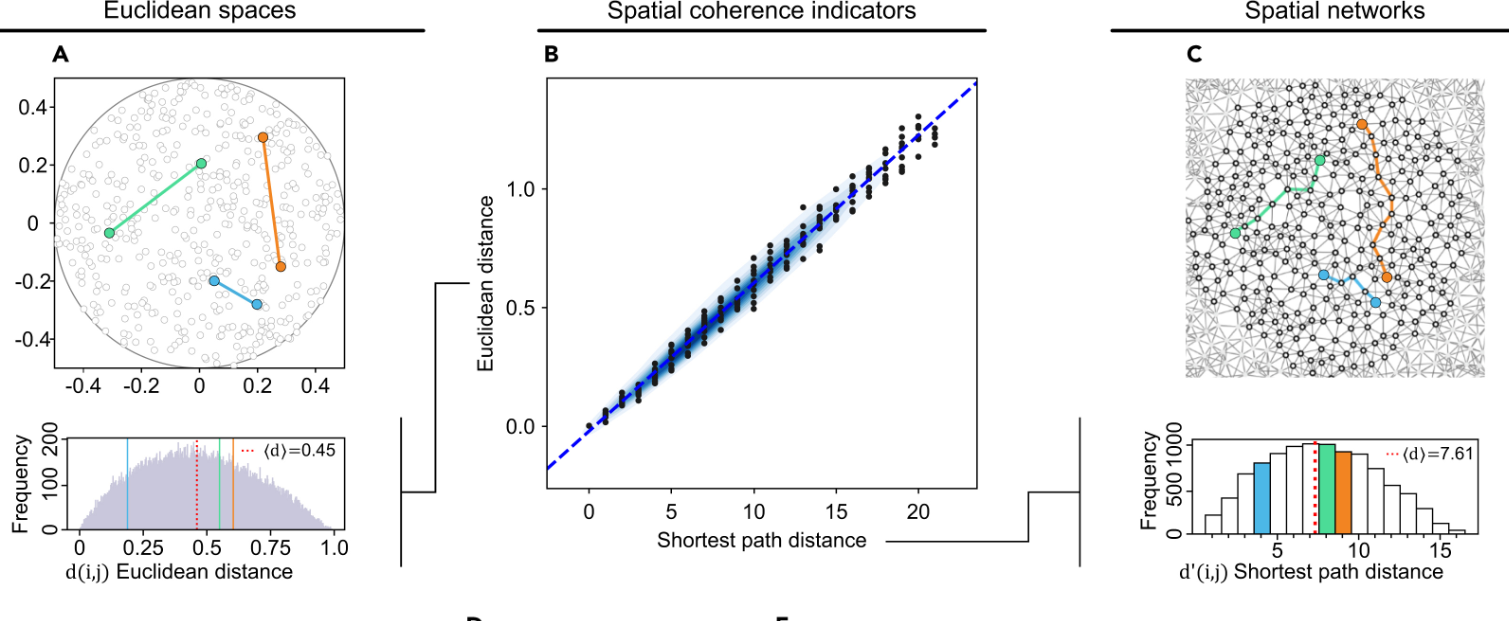

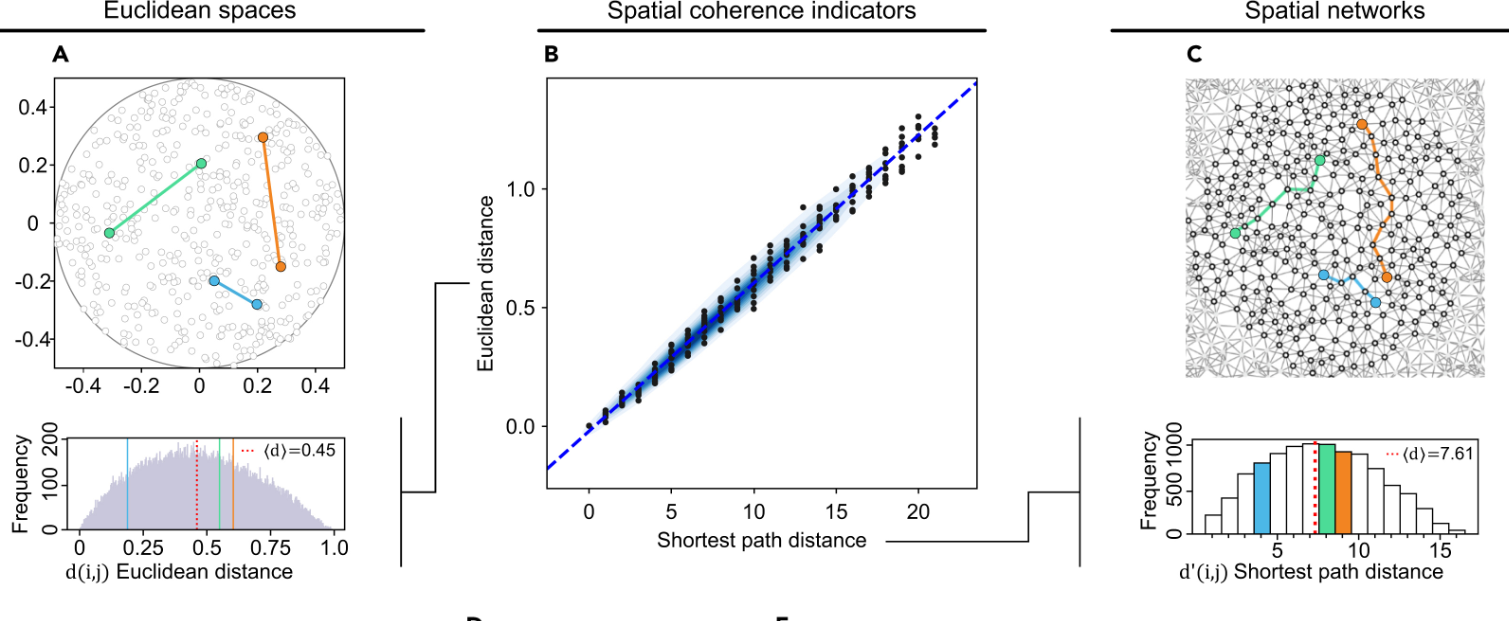

Understanding spatial networks addresses a core problem shared across biology, physics, and data science: how reliable geometric information can emerge from local interactions alone.

Many natural and engineered systems do not provide direct access to coordinates, but instead encode space implicitly through patterns of connectivity, proximity, or interaction.

Our work focuses on identifying the principles that make such networks reconstructable, asking when and why a network genuinely reflects an underlying physical or

geometric space rather than an abstract graph. Central to this is the concept of spatial coherence, which captures whether network distances behave consistently with

geometric constraints such as dimensionality, scaling, and geodesic structure.

By studying how shortest path distances, spectral properties, and scaling laws relate to physical space, we seek to distinguish networks that preserve spatial meaning

from those distorted by noise, shortcuts, or missing information.

Beyond reconstruction itself, spatial networks raise broader questions about robustness, noise tolerance, and design. Real networks often contain false or long range connections, uneven sampling, or heterogeneous density, all of which can blur spatial structure. Rather than treating these effects as purely detrimental, we study how network properties such as connectivity and redundancy influence the balance between signal and distortion. This perspective allows us to develop ground truth free quality control measures and principled ways to assess whether a dataset is likely to support reliable spatial inference. More generally, our research aims to establish a theory of spatial networks that applies across modalities, from molecular and cellular systems to sensor networks and abstract embeddings, providing tools to reason about space when space itself is not directly observed.

Related Publications & Links:

- Bonet DF, Blumenthal JI, Lang S, Dahlberg SK, Hoffecker IT. Spatial coherence in DNA barcode networks. Patterns. 2025 Dec 12;6(12).

cell.com

- Bonet DF, Hoffecker IT. Image recovery from unknown network mechanisms for DNA sequencing-based microscopy. Nanoscale. 2023;15(18):8153-7.

pubs.rsc.org

- Hoffecker IT, Yang Y, Bernardinelli G, Orponen P, Högberg B. A computational framework for DNA sequencing microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019 Sep 24;116(39):19282-7.

pnas.org

Network-based 2D Spatial Transcriptomics

Spatial transcriptomics is a set of technologies that makes it possible to measure which genes are active in a

tissue while preserving their physical locations. This matters because biological function is not determined by gene

activity alone, but by how different cell types are arranged, interact, and form structures such as layers, gradients,

and microenvironments. By adding spatial context to gene expression measurements, spatial transcriptomics allows researchers

to study tissue organization in development, cancer, and disease, and to connect molecular programs to anatomy in a direct

and quantitative way.

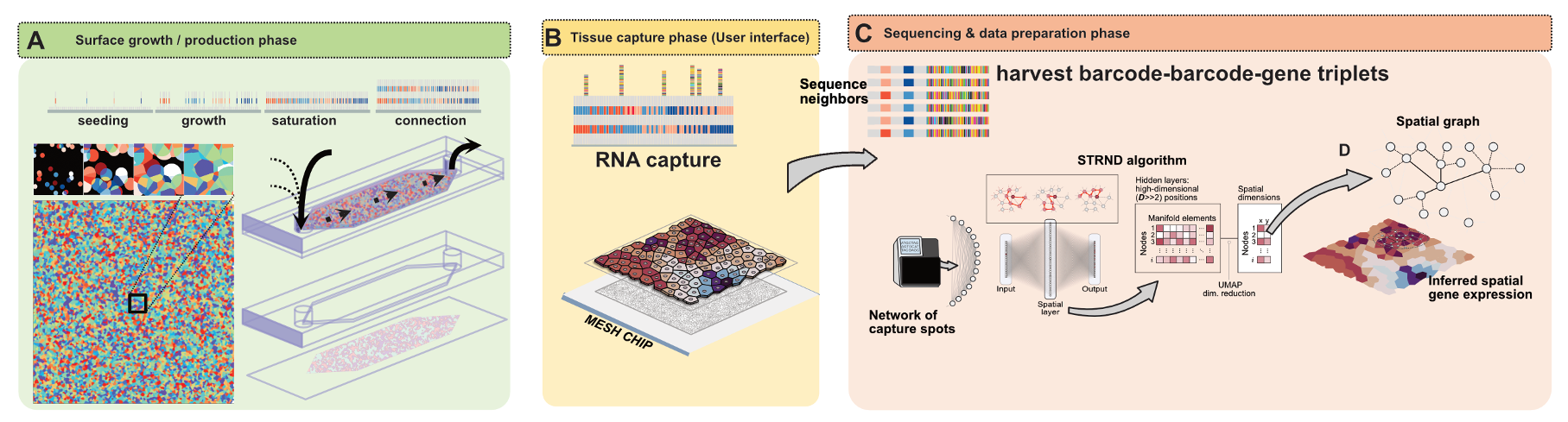

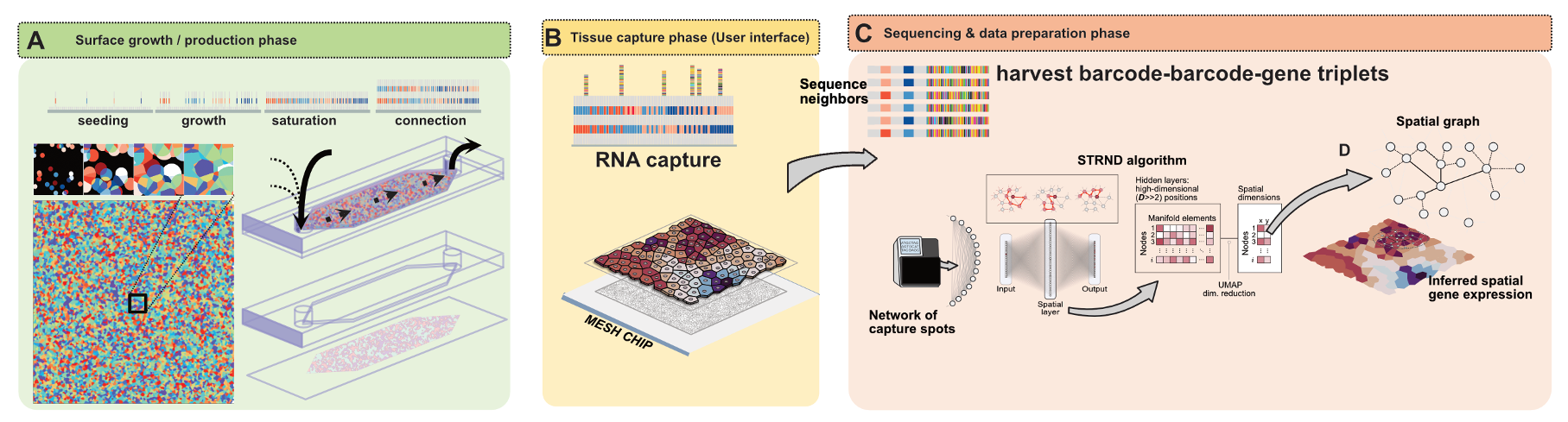

Network based 2D spatial transcriptomics is an emerging class of approaches that encodes spatial information implicitly through molecular

proximity rather than explicitly through pre defined coordinates.

Instead of relying on printed grids, lithography, or optical decoding to assign positions,

these methods generate dense collections of molecular capture sites whose local neighborhood relationships are recorded in sequencing data. By reading out which molecular barcodes tend to appear together due to physical proximity on a surface, one obtains a graph whose structure reflects the underlying tissue geometry.

Spatial positions are then inferred computationally by reconstructing a two dimensional layout that is most consistent with the observed network connectivity,

in close analogy to recovering a map from a list of local connections.

This network based perspective shifts spatial transcriptomics from a manufacturing problem to an inference problem.

Spatial resolution and mapped area are no longer fixed by the precision of fabrication, but instead emerge from the density and quality of local connections

in the network and from the reconstruction algorithms applied downstream. As a result, these approaches offer a path toward large area, high throughput spatial

profiling using simple, self assembled capture surfaces combined with standard sequencing. More broadly, network based spatial transcriptomics connects molecular

biology with graph theory and statistical inference, opening new opportunities to study tissue organization, gradients, and multicellular structure at scale while

reducing cost and technical complexity.

Related Publications & Links:

- Benson E, Hoffecker IT. Capture surface of metapolonies. Swedish Patent SE547614C2. Application filed January 15, 2024. Published October 28, 2025.

patents.google.com

- Hoffecker IT, Yang Y, Bernardinelli G, Orponen P, Högberg B. A computational framework for DNA sequencing microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019 Sep 24;116(39):19282-7.

pnas.org

- Two researchers in Sweden to receive an ERC Proof of Concept Grant

www.vr.se

- Spatial transcriptomics chips with sequencing-based microscopy

cordis.europa.eu

- Dahlberg SK, Bonet DF, Franzén L, Ståhl PL, Hoffecker IT. Hidden network preserved in Slide-tags data allows reference-free spatial reconstruction. Nature Communications. 2025 Oct 31;16(1):9652.

nature.com

3D Molecular Reconstruction by Sequencing-based Microscopy

Three dimensional molecular imaging aims to reveal how cells, genes, and biomolecules are organized and interact inside

intact tissues and organs. This spatial context is essential for understanding development, disease progression, and how

complex biological functions emerge from local interactions. Today, most high resolution 3D imaging relies on optical microscopy,

which faces fundamental challenges as samples become thicker and more complex. Light scattering, absorption, limited penetration depth,

and the need for elaborate clearing or sectioning protocols constrain resolution, throughput, and scalability. As a result, many biological

systems remain difficult or impossible to image comprehensively in three dimensions using optics alone.

Our research explores an alternative route to 3D molecular imaging that does not rely on lenses or light. Instead of measuring spatial

position directly, we encode spatial proximity into networks of interacting molecular barcodes. When molecules are close together in

physical space, they are more likely to interact, co associate, or be captured together. By reading out these interactions using high

throughput DNA sequencing, we obtain large molecular networks whose connectivity reflects the underlying three dimensional structure of the

sample. In this framework, spatial information is stored implicitly in who is connected to whom, rather than explicitly in pixels or voxels.

From these molecular networks, we reconstruct three dimensional spatial organization computationally. Using graph based inference,

we recover layouts that are most consistent with the observed connectivity patterns, effectively rebuilding a 3D map from local neighborhood

relationships alone. This network based, optics free approach shifts 3D microscopy from a hardware limited imaging problem to a data driven

inference problem. It opens a path toward scalable, tissue scale, and potentially whole organ molecular imaging using sequencing as the primary

readout, with resolution and volume determined by network density and molecular design rather than by optical constraints.

Related Publications & Links:

- Bonet DF, Blumenthal JI, Lang S, Dahlberg SK, Hoffecker IT. Spatial coherence in DNA barcode networks. Patterns. 2025 Dec 12;6(12).

cell.com

- Bonet DF, Hoffecker IT. Image recovery from unknown network mechanisms for DNA sequencing-based microscopy. Nanoscale. 2023;15(18):8153-7.

pubs.rsc.org

- Instrument-free 3D molecular imaging with the VOLumetric UMI-Network EXplorer

cordis.europa.eu

- VOLUMINEX Project Webpage

voluminex-project.eu/

- SciLifeLab-led consortium receives Pathfinder grant to enable sequencing-based microscopy in 3D

scilifelab.se

- KTH med och delar på 11,7 miljoner euro till deep tech

kth.se

- The Future of 3-D Molecular Imaging in Life Sciences with Ian Hoffecker

singletechnologies.com

Technology & Evolutionary Computation

Technology can be understood as a form of computation carried out in the physical world. Every technological process encodes rules, constraints, and memory, and unfolds through sequences of conditional actions, much like a program being executed. Over time, technological designs change through processes that closely resemble biological evolution: variants are generated, tested through interaction with their environment, and selectively retained. Innovation in this view is not a single moment of invention, but an evolutionary process shaped by variation, selection, and inheritance. This perspective allows technologies, from molecular systems to large-scale material practices, to be studied as evolving populations governed by general principles of information processing.

Our research explores these principles at a fundamental level by developing formal models of technology as a generative process. We study how structured designs arise from sequences of dependent operations, how techniques and subcomponents are reused across different constructions, and how material outcomes preserve only partial information about the processes that produced them. By framing technological production as a stochastic, hierarchical process with hidden internal organization, we aim to understand both how complex technological systems emerge and what can be inferred about them from incomplete physical evidence.

These ideas also inform our interest in evolutionary computation as a design strategy in molecular programming. Through selected collaborations, we engage with systems where variation and selection are used to explore functional design spaces, such as DNA-based molecular binders shaped through iterative selection. In this context, evolutionary processes serve as both a conceptual model and a practical tool, illustrating how computation, adaptation, and physical implementation can coincide. This research theme situates evolutionary computation as a unifying lens for understanding technology across scales, without treating any single application domain as its primary focus.

Related Publications & Links:

- Benson E, Hoffecker IT. Random DNA structures. International Patent Application WO2024260866. Application filed June 14, 2024. Published December 26, 2024.

patentscope.wipo.int

- Hoffecker JF, Hoffecker IT. Technological complexity and the global dispersal of modern humans. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 2017 Nov;26(6):285-99.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- Hoffecker JF, Hoffecker IT. Measuring the computational complexity of artifact design in Paleolithic archaeology.

researchgate.net

- Hoffecker JF, Hoffecker IT. The structural and functional complexity of hunter-gatherer technology. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 2018 Mar;25(1):202-25.

link.springer.com

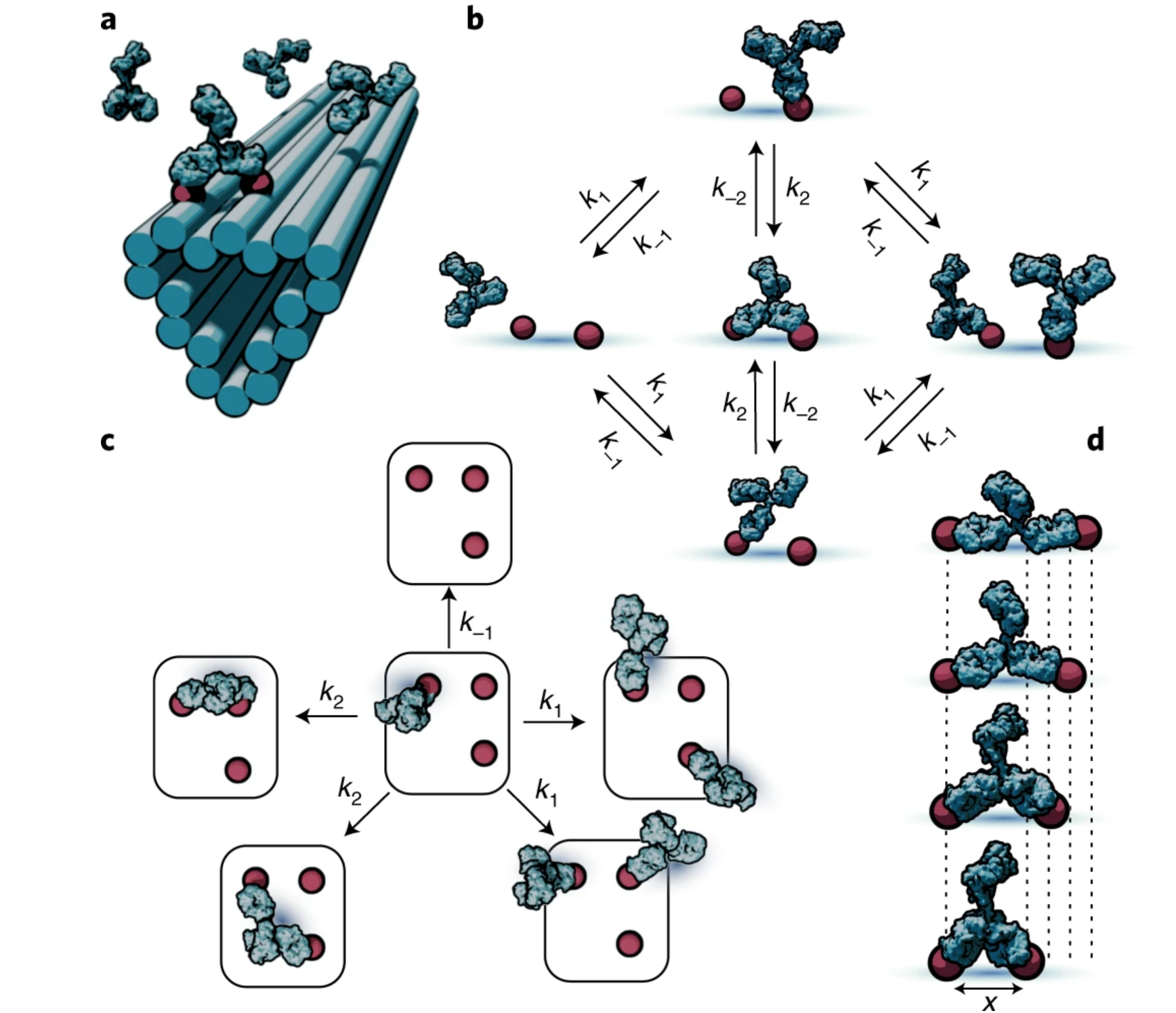

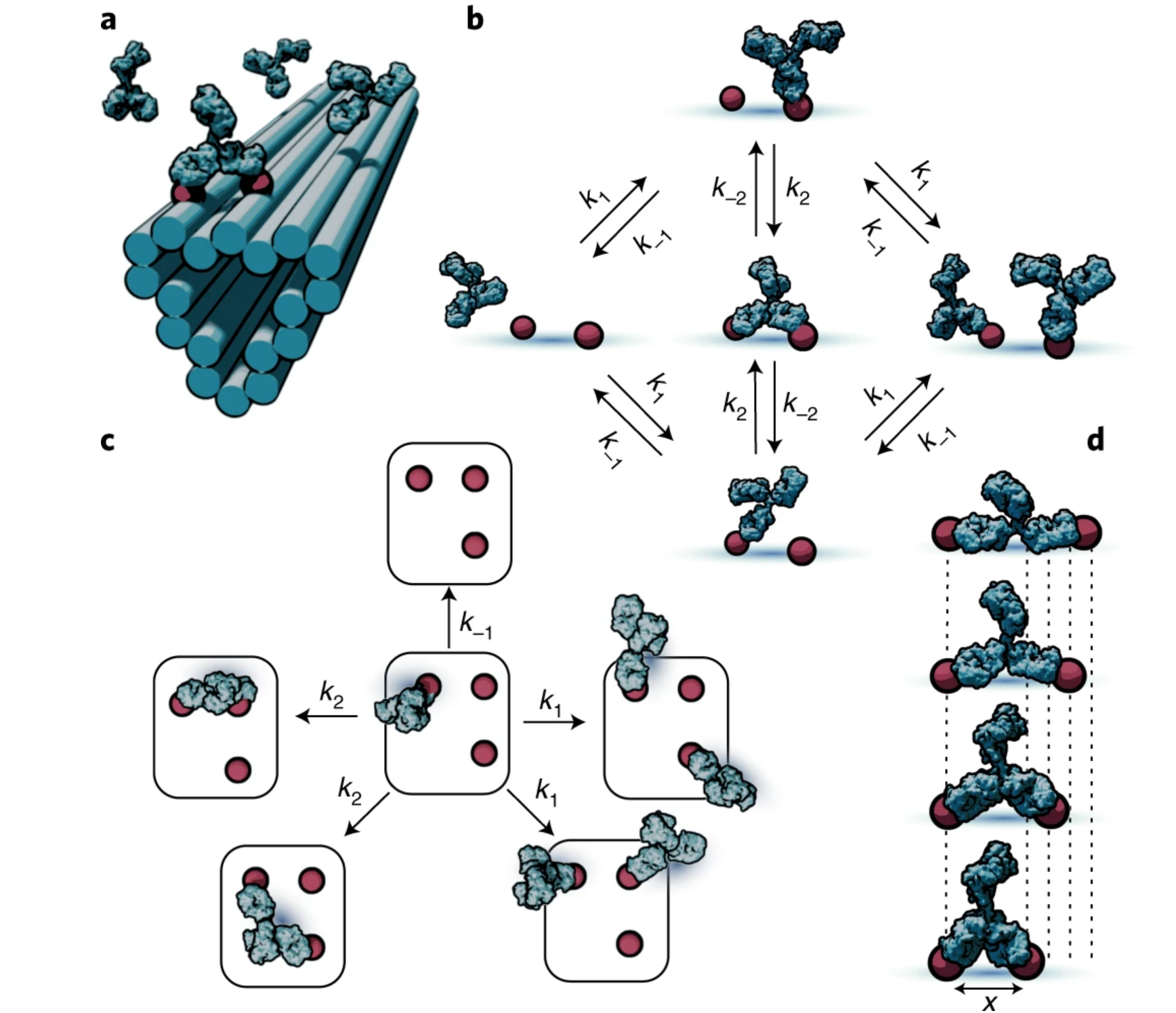

Spatially Programmed Immunochemistry

At the most basic level, this research asks a simple question:

how does the immune system sense and respond to the spatial

arrangement of molecules, not just their chemical identity?

In living systems, many biological signals are encoded in patterns.

Viruses, bacteria, and synthetic vaccines often present antigens

in highly organized nanoscale arrays, and immune receptors do not

bind these patterns passively. Instead, they physically explore them.

By creating precisely controlled molecular landscapes,

we can study how antibodies move, bind, and cooperate across space,

revealing rules that are otherwise hidden in complex biological environments.

To access these rules, we use DNA nanotechnology as a molecular

construction toolkit. DNA origami allows us to position antigens

with nanometer precision and to systematically vary their spacing

and geometry. By combining these engineered patterns with

quantitative biophysical measurements, we can directly measure

how antibody binding strength, flexibility, and multivalent

interactions depend on spatial organization. This approach has

shown that antibody binding is not governed by a single optimal

distance, but instead reflects a range of spatial tolerances that

depend on antibody class, affinity, and geometry. In this way,

spatial patterning becomes a controllable variable rather than an

uncontrolled feature of biology .

More broadly, this work connects to our group’s central theme

of molecular programming. Rather than viewing molecules as

isolated actors, we treat them as components in a programmable

system, where function emerges from arrangement, connectivity,

and interaction rules. By designing molecular patterns that

encode specific spatial and kinetic constraints, we effectively

write programs that antibodies and other biomolecules execute

through physical interactions. This perspective links immune

recognition to a wider framework of molecular computation,

where nanoscale structure serves as both information storage

and instruction set, guiding biological behavior through

designed molecular geometry.

Related Publications & Links:

- Shaw A, Hoffecker IT, Smyrlaki I, Rosa J, Grevys A, Bratlie D, Sandlie I, Michaelsen TE, Andersen JT, Högberg B. Binding to nanopatterned antigens is dominated by the spatial tolerance of antibodies. Nature nanotechnology. 2019 Feb;14(2):184-90.

nature.com

- Hoffecker IT, Shaw A, Sorokina V, Smyrlaki I, Högberg B. Stochastic modeling of antibody binding predicts programmable migration on antigen patterns. Nature computational science. 2022 Mar;2(3):179-92.

nature.com

- Model shows how antibodies navigate pathogen surfaces like a child at play

eurekalert.org

- DNA origami: A precise measuring tool for optimal antibody effectiveness

sciencedaily.com

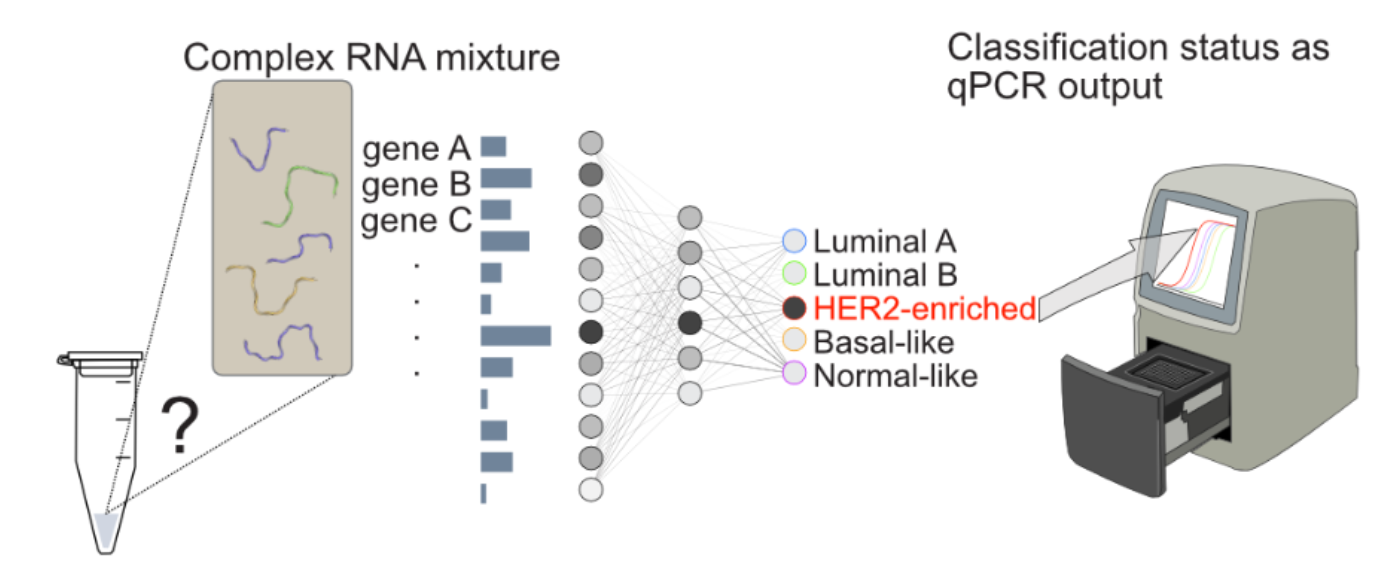

DNA-based Chemical Neural Networks

Living cells already process information using chemistry: molecules bind,

react, and amplify signals to make decisions such as when to divide,

differentiate, or respond to stress. DNA-based computing takes inspiration

from this natural logic and asks whether we can deliberately program

molecules to carry out information processing tasks. Instead of electrons

flowing through silicon circuits, information is represented by the

presence and relative amounts of DNA strands, and computation happens

through predictable chemical interactions between them. This opens the

possibility of performing complex decision making directly inside a test

tube, using the same molecular language as biology itself.

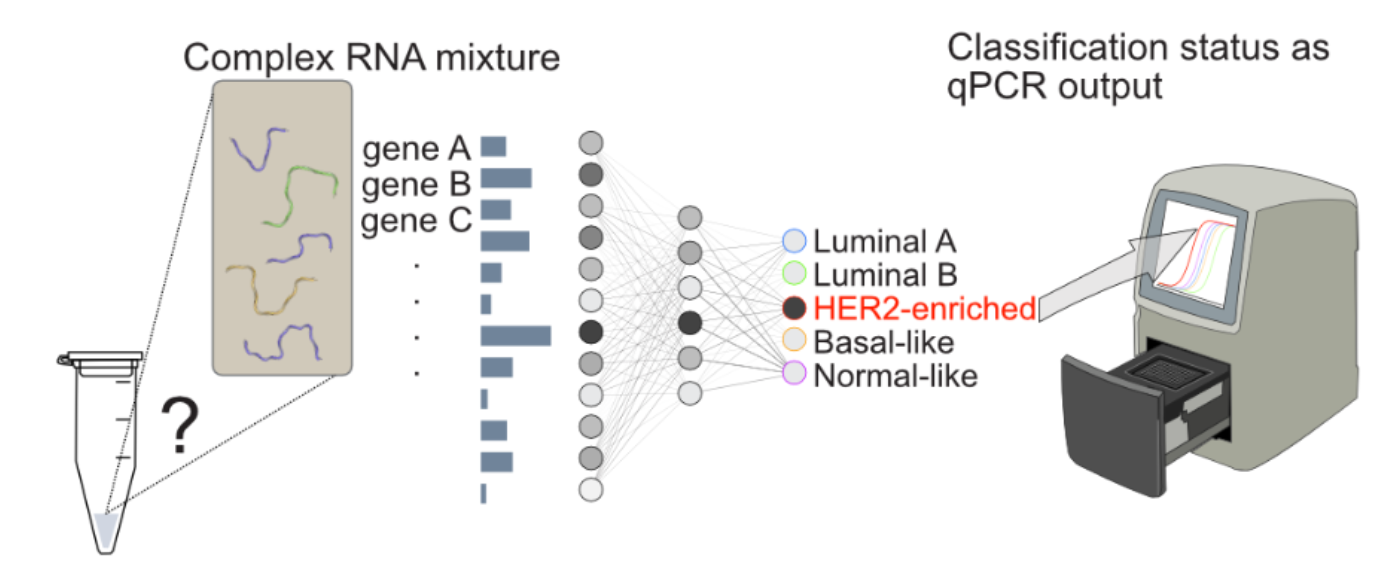

In our work, we explore how concepts from artificial neural networks

can be translated into DNA chemistry. In a neural network, information

flows through weighted connections and nonlinear activation steps to

recognize patterns rather than single signals. We recreate these ideas

using DNA sequence design and enzymatic reactions. The strength of

interaction between different DNA strands plays a role similar to

connection weights, while polymerase-driven amplification introduces

nonlinear responses analogous to neural activation. By carefully

designing these molecular interactions, we can build chemical systems

that respond to combinations of inputs, not just the presence or absence

of one molecule.

This approach is especially powerful for diagnosing complex diseases

such as breast cancer, where clinically relevant information is often

encoded in patterns of gene expression rather than single biomarkers.

Today, recognizing these patterns typically requires sequencing and

heavy computational analysis. Our goal is to shift part of that

intelligence into chemistry itself. By constructing DNA-based neural

networks that directly process mixtures of nucleic acids associated

with disease states, we aim to create fast, low-cost diagnostic

reactions that output an interpretable molecular signal. In the

long term, this could help bring sophisticated pattern-based diagnostics

closer to the patient, without the need for centralized sequencing

infrastructure.

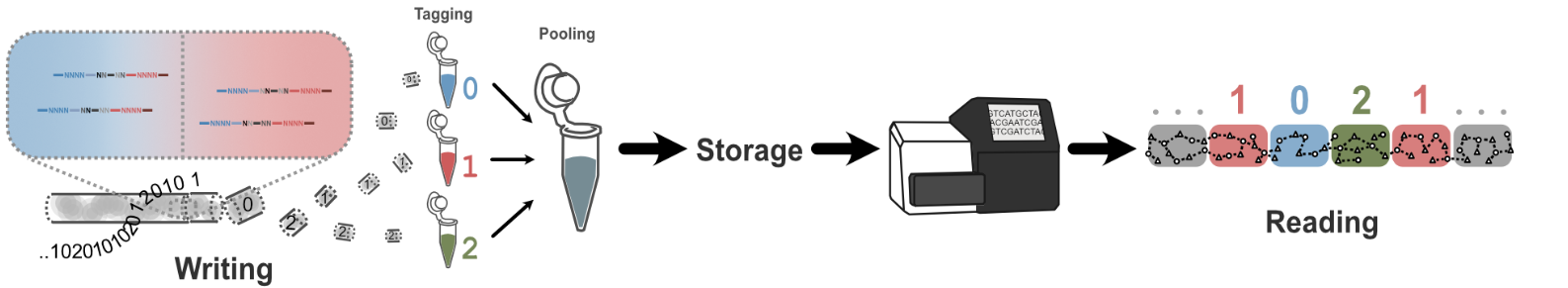

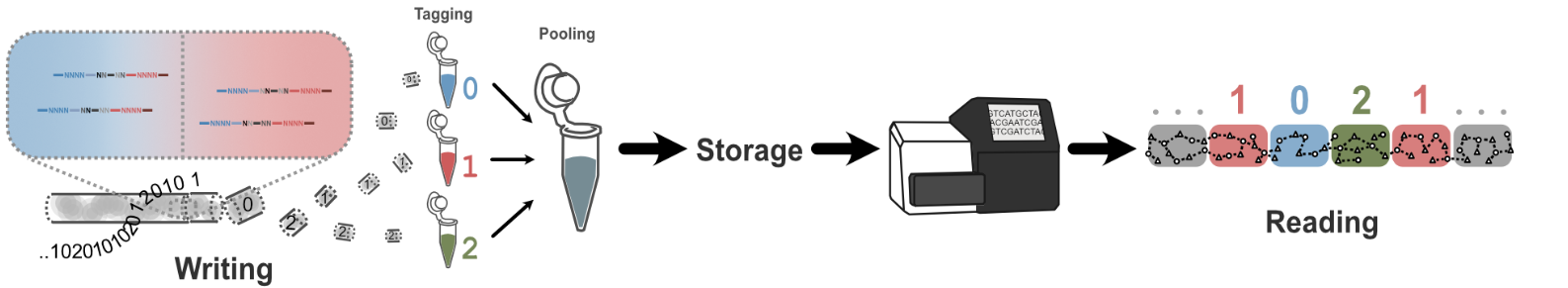

Digital Data Storage in DNA

Dna has emerged as an intriguing medium for long-term information storage.

It is extraordinarily dense, stable over geological timescales, and already

manufactured and copied at massive scale by biology.

However, translating these advantages into a practical data storage technology

is still challenging.

Current approaches face bottlenecks related to writing cost and speed

and the difficulty of scaling.

Many of these limitations arise because dna data storage has often been treated as

a linear pipeline. Information is encoded into sequences, synthesized, stored,

and later sequenced and decoded, with each step optimized largely in isolation.

This view struggles with issues such as uneven sequence usage, loss of molecules,

amplification bias, and the growing overhead required for error correction and

indexing as datasets become larger. As a result, there is a widening gap between

elegant proof of concept studies and storage architectures that could operate

robustly in realistic settings.

Our research explores an alternative perspective that treats DNA data

storage as a distributed and structured system rather than a

collection of independent strands. Instead of relying on single sequences

carrying isolated pieces of information, we investigate ways in which

information can be shared, reinforced, and recovered through patterns of

relationships between many molecules. By taking inspiration from networked

systems, we aim to develop multiple complementary strategies that improve

robustness, scalability, and readout efficiency while remaining compatible

with existing molecular tools. These ideas open the door to dna storage

architectures that circumvent the limitations of classical direct storage with

DNA synthesis.